Ira Aldridge: Theatrical Trailblazer

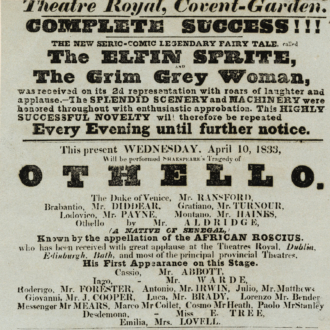

Playbill, Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, April 10, 1833 (detail)

A nineteenth-century playbill such as this one announced which shows would be performed each night, which actors were involved, and some of the highlights the audience could expect. In 1833, Ira Aldridge was offered the chance to play the title role of Shakespeare’s Othello at Covent Garden, one of London’s most prestigious theatres, when Edmund Kean, who had been scheduled to perform the role, suddenly fell ill. (Kean, who was perhaps the most celebrated British actor of his day, died shortly thereafter.) This playbill announces Aldridge’s first performance. Aldridge had played Othello in smaller theatres and in other cities around England, but neither he nor any Black actor had played a lead role on one of London’s premier stages before.

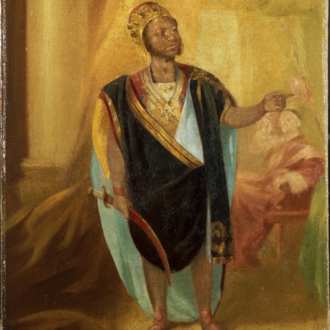

Ira Aldridge, Possibly in the Role of Othello

William Mulready (Irish, 1786–1863)

ca. 1826

oil on panel, 1515⁄16 × 113⁄4 in.

Ira Aldridge is believed to have been born in New York City around 1807 (though some early biographies say he was born in Bel Air, Maryland), the son of a free Black preacher named Daniel and his wife Luranah. Although there were some theatre opportunities for African-Americans in New York, including The African Company, which is considered this country’s first black troupe, acting was not a financially feasible career choice for a young Black man in America, so Ira Aldridge moved to England. Artist William Mulready painted this oil painting around 1826, when Aldridge would have been around 19 years old, about one year after Aldridge’s first performances in England.

Othello, the Moor of Venice

James Northcote (English, 1746–1831)

1826

oil on canvas, 30 × 25 in.

At age 19, Ira Aldridge had already played Othello in second-tier or working-class theatres around London (including the Coburg Theatre, still standing today under the name The Old Vic), and he went on a tour of smaller English cities. He performed in Manchester in 1827. Manchester was a center for the English anti-slavery movement and this portrait was the first-ever purchase by the Royal Manchester Institution. The painter, later a member of the Royal Academy of Artists, uses a masterful range of colors to create a romantic, evocative portrait of a man, avoiding both elaborate exotic costumes commonly associated with Othello and the flat, dark paint often used by artists of his time to paint people of African ancestry.

Ira Aldridge as Othello

Henry Perronet Briggs (English, ca. 1791–1844)

ca. 1830

oil on canvas, 501⁄2 × 403⁄4 in.

This portrait now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., along with portraits of U.S. Presidents, Supreme Court justices, and cultural luminaries like Louis Armstrong, Maya Angelou, and Michael Jackson. Paintings of celebrity actors “in character” and in costume were very popular among the wealthy in the early 1800s. Less wealthy fans could purchase prints, and illustrations of famous actors were featured at the front of printed scripts. Art historians are uncertain if Aldridge “sat” for Briggs, or if Briggs painted this portrait from memory.

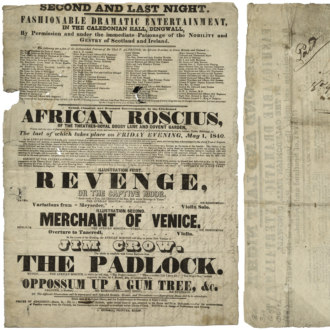

Playbill, Dingwall Theatre, Scotland, May 1, 1840, with handwritten letter on reverse

In Dingwall, Scotland, Aunt B. went to see Aldridge’s performance in 1840 and penned a letter on the back of a playbill to her niece, Miss M., in Westminster, London. The aunt wrote, “Witnessed the performance of Zanga last evening. The audience was respectable—but with the exception that he dressed and looked the Moor it was otherwise contemptible…” While Aldridge was successful with many audiences, there were always critics who lacked the ability to see Aldridge as anything more than a man of color, and preemptively denied any possibility that he might demonstrate a high level of artistry.

Ira Aldridge as Othello in ‘Othello’ by William Shakespeare

artist unknown

ca. 1848

oil on canvas, 167⁄8 × 131⁄2 in.

This small painting was made in England around 1848 by an anonymous artist. It again shows Aldridge in costume, probably for the role of Othello, and is in the permanent collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum, named after England’s nineteenth-century Queen who was herself an avid theatre-goer. Aldridge became a naturalized English citizen and subject of Queen Victoria in 1863.

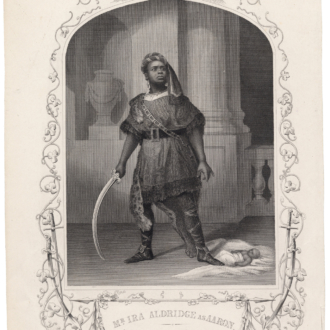

Mr. Ira Aldridge as Aaron

engraving from a daguerreotype by Paine of Islington

ca. 1852/53

10 × 61⁄4 in.

London: London Printing and Publishing Company

In addition to Othello, Aldridge famously played another “black” Shakespeare character, Aaron the Moor from Titus Andronicus. In Shakespeare’s original text, Aaron is a villain: one of Titus’s enemies, the secret lover of Queen Tamora, and a liar directly responsible for several deaths in the play. Aldridge re-wrote large sections of Titus Andronicus to make Aaron a heroic, noble character. Famous eighteenth- and nineteenth-century actors and directors frequently adapted Shakespeare’s work. (White British actor/manager David Garrick re-wrote The Taming of the Shrew to assign all Kate’s best lines to himself, and Nahum Tate gave the tragedy of King Lear a happy ending.) None of these, however, tried to reclaim and humanize the character of the outsider, the minority, or the “exotic other” the way Aldridge’s adaptation choices did.

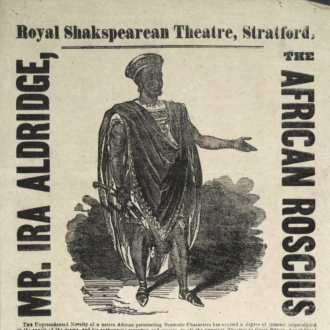

Playbill, Royal Shakespearean Theatre, Stratford, April 28, 1851

Aldridge’s main success as an actor came in touring towns outside London. On April 28, 1851, he performed at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Shakespeare’s birthplace of Stratford-upon-Avon. This playbill includes a biography that blends fact and fiction: tales that his grandfather was a Senegalese emperor overthrown in a mutinous uprising appear to be sensational fiction put forward by Aldridge himself. It was common practice for actors to invent elaborate life stories to make themselves seem more interesting—and to sell more tickets—to theatre-goers.

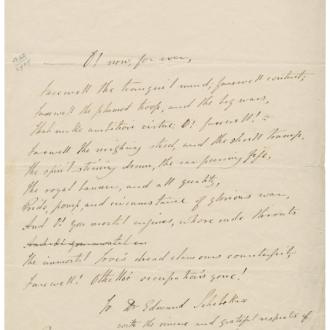

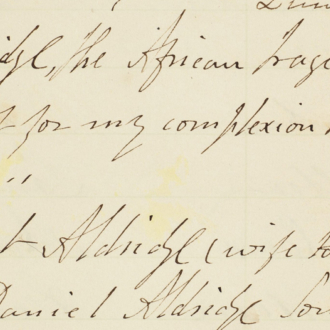

Lines from act III, scene 3 of Othello, handwritten by Ira Aldridge, dated May 10, 1853

Othello remained a signature role for Aldridge. This passage is from act III, scene 3 of Othello, a dramatic scene in which Othello begins to abandon his former ideals, including his devotion to military heroism, after a villainous associate tells him falsely that Othello’s adored wife has been unfaithful. Aldridge hand-wrote this passage and addressed it to his friend Dr. Edmund Schebek, a lawyer and historian he had met in the Czech city of Prague. The actor autographed it “with the sincere and grateful respects of Ira Aldridge.”

The text (lines 399–409) reads:

O! now, forever

Farewell the tranquil mind; farewell content;

Farewell the plumed troop, and the big wars

That make ambition virtue: O! farewell!

Farewell the neighing steed, and shrill trump,

The spirit-stirring drum, the ear piercing fife,

The royal banner, and all quality,

Pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war!

And O! you mortal confines, whose rude throats

The immortal Jove’s dead clamours counterfeit,

Farewell! Othello’s occupation’s gone!

Ira Aldridge as Othello

lithograph by S. Bühler, Mannheim, Germany, from a photograph by J. Chailloux

1854

12 × 91⁄2 in.; hand-colored

This fine example of a print has been hand-colored to give it a more life-like appearance and shows another version of Aldridge’s signature Othello costume. Note Aldridge’s autograph, addressed to Herr Weber, “with the kindest regards of Ira Aldridge.” Aldridge counted among his admirers many people from what are present-day Germany, Poland, and Russia, where he toured extensively. When he performed in these countries, he typically delivered his lines in English while fellow cast members performed in their own languages.

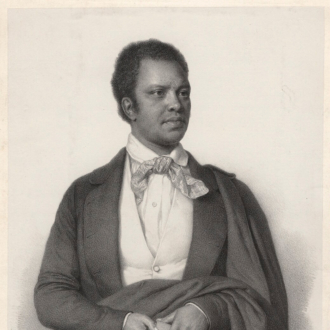

Ira Frederick Aldridge

lithograph by Nicolas Barabas

1853

173⁄8 × 111⁄2 in.

Here, Aldridge does not appear “in character” but instead holds a book, a long-time symbol that the subject in the portrait was well-educated and intellectual. As Aldridge received international recognition and honors, printers updated earlier illustrations to showcase his awards. A later version of this illustration titled “Ira Aldridge, African Tragedian” is almost identical but shows the addition of medals and ribbons around his neck and an updated inscription: “Member of the Order of Art and Science conferred by His Majesty King William 4th of Prussia, holder of the Medal of Leopold, and the White Cross, etc., etc.”

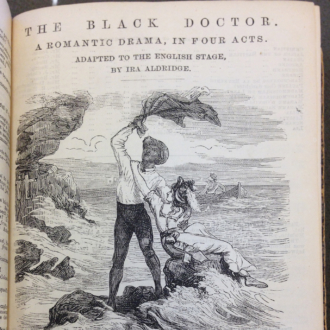

Published script of The Black Doctor: A Romantic Drama in Four Acts, adapted into English by Ira Aldridge

Dicks’ Standard Plays, no. 460

crown octavo booklet, approx. 71⁄2 in. high; 18 pages

London: John Dicks, ca. 1883

Aldridge was also a playwright. He created his adaptation of the romantic melodrama The Black Doctor, based on the contemporary French play Le Docteur noir by Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois, around 1847. Aldridge himself played “Fabian,” the Black Doctor, a former slave who uses both medical knowledge and heroic strength to save the lives of many neighbors, including a white aristocratic woman named Pauline. They fall in love but their happiness is doomed by her disapproving family, false imprisonment, madness, and a series of other misfortunes. Interracial marriage was a fascinating topic to English audiences. While interracial couples often faced prejudice, the English did not have laws like those in America that made interracial marriage illegal. The topic had special relevance to Aldridge. His first wife, Margaret, was a white woman from northern England; after her death, he married a white Swedish opera singer named Amanda.

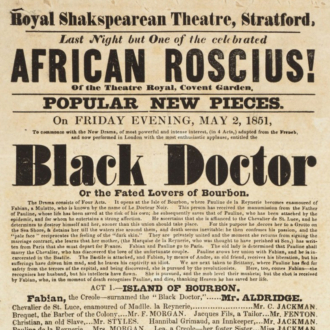

Playbill, Royal Shakespearean Theatre, Stratford, May 2, 1851

For Aldridge’s performance at the Royal Shakespearean Theatre in 1851, the audience could look forward to Aldridge’s stirring tragic performance in The Black Doctor plus “a laughable farce (written expressly for Mr. Ira Aldridge) entitled Stage Mad!!” It was common to follow a serious drama with a comic afterpiece and some singing—an actor’s ability to execute both tragic romance and musical comedy pleased the audience and showed off the actor’s own range. Aldridge also often performed comic songs like “Possum up a Gum Tree” that built on vaudeville, music hall, and minstrelsy traditions. Scholars have also documented instances of Aldridge closing many performances with a direct address, song, or poem advocating for the abolition of slavery.

Inscription by Ira Aldridge in the visitors’ book at Shakespeare’s birthplace, dated May 2, 1851

On the same day that he appeared at the old Royal Shakespearean Theatre in The Black Doctor, May 2, 1851, Aldridge signed the guest book during a visit to Shakespeare’s birthplace with his wife Margaret and son Ira Daniel Aldridge. Margaret’s home is listed as “London,” while Ira Aldridge notes his as Senegal, Africa, in keeping with his invented life story that he was a Senegalese prince in exile. Below his name he inscribed a line spoken by the character of the Prince of Morocco in act II of The Merchant of Venice: “Mislike me not for my complexion, the shadowed livery of the burnish’d sun.”

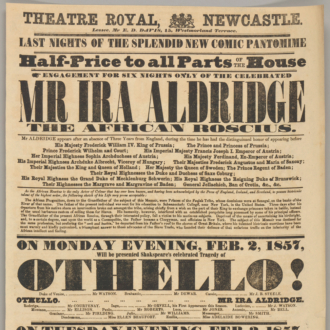

Playbill, Theatre Royal, Newcastle, February 1857 (detail)

Returning from a European tour to play the Theatre Royal in Newcastle (in northern England) in 1857, Aldridge’s playbill featured three of his signature roles. On Monday, he played Othello, his most famous part. On Tuesday, he played the part of “Gambia” in The Slave, and on Wednesday night, he played Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. The Slave was a popular melodrama of its day, centering on the brotherly bond between the fictional characters of an enslaved African named Gambia and his white friend Clifton. In many of his non-Shakespearean roles, Aldridge played a slave or servant character whose humanity, nobility, and intelligence is exhibited throughout the play, and served as a direct challenge to concepts of white “superiority.”

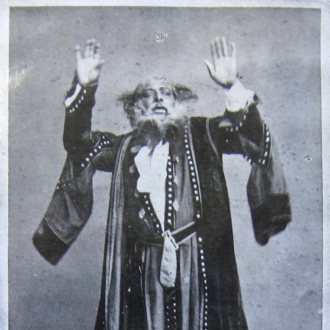

left:

Ira Aldridge as Othello

photograph; date and location unknown

right:

“The Chevalier Ira Aldridge as Othello”

engraving; date unknown

These undated images again show Aldridge posing in costume for Othello. Although access to photography gradually increased during Aldridge’s lifetime, prints made from etchings or lithographs were often sharper and were easier for printers to mass-reproduce. Frequently, the engravers and printers placed less emphasis on reproducing a person’s face accurately than on capturing decorative details, and sometimes simply updated or re-used older generic templates. By the time the engraving was printed, Aldridge had been awarded a knighthood in Europe been granted use of the title “Chevalier.”

Ira Aldridge as Shylock

photograph by I. Asanova (?)

Saint Petersburg, 1858

Ira Aldridge lived as a sophisticated expatriate, never returning to the United States but meeting numerous poets, authors, and artists during his many years abroad. In 1858 Aldridge’s European tour took him to Russia, where his performances in such roles as Othello, Shylock, and Lear were enthusiastically received. As with his revision of the character of Aaron in Titus Andronicus, Aldridge substantially re-wrote sections of The Merchant of Venice to make Shylock more a victim than a villain. On other occasions he even wore “white-face” makeup to play such parts as Lear and Richard III.

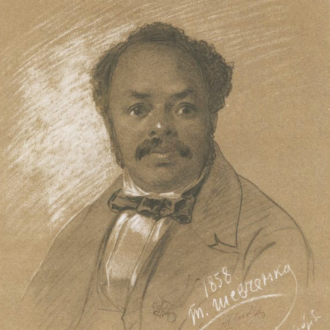

Drawing of Ira Aldridge

Taras Shevchenko (Ukrainian, 1814–1861)

1858

Italian and white pencil on stained paper, 133⁄8 × 105⁄8 in.

While in Russia Aldridge had his portrait drawn by the influential Ukrainian poet and artist Taras Shevchenko. The two became acquainted through their mutual friend Leo Tolstoy, author of War and Peace and Anna Karenina. This sort of “celebrity meets celebrity” interaction was not uncommon. For instance, after encountering Aldridge in Paris, Danish fairy tale author Hans Christian Andersen later wrote: “We shook hands and exchanged a few politenesses in English. I admit that it pleased me to have one of Africa’s gifted sons hail me as a friend.”

Ira Aldridge

photograph; date and location unknown

In this photograph, one of the few taken of Aldridge out of theatrical costume, he wears two of his medals. Here, as often elsewhere, he is referred to as “the African Roscius,” a title he started using early in his career. Roscius was the name of a famous Roman actor whose talent helped him earn freedom from slavery; he died in 62 BCE. Celebrity (and “wanna-be” celebrity) actors often adopted the title of “Roscius”: child actors were sometimes labeled “Young Roscius” or “Infant Roscius” and there was at least one actress referred to as “the Female Roscius.” By calling himself the “African Roscius,” Aldridge also helped to reinforce his invented family history as Senegalese royalty.

Othello

Pietro Calvi (Italian, 1833–1884)

ca. 1873

marble and bronze, approx. 345⁄8 × 221⁄16 × 2213⁄16 in.

This life-size bust represents Othello, holding his wife’s handkerchief at the moment he realizes that she is innocent. Note the tear on his cheek. At a time when nineteenth-century artworks in the “orientalist” or “ethnographic” tradition often depicted Asian or African people as exotic, lazy, or savage types, Calvi produced a thoughtful, emotional portrait of an individual. Although it was crafted shortly after Aldridge’s death, it was almost certainly inspired by Aldridge. Aldridge’s image had circulated widely in print; he was famous across Europe as the pre-eminent African-American actor and most recognizable actor to play Othello.

Illustration from Ira’s Shakespeare Dream (detail)

Floyd Cooper (American, b. 1956)

ca. 2015

oil wash on board

from Ira’s Shakespeare Dream by Glenda Armand

New York: Lee and Low Books, 2015

Ira Aldridge continues to inspire. In her children’s book Ira’s Shakespeare Dream, published in 2015, Glenda Armand tells Aldridge’s story in a format designed for young readers. In this illustration from the book, Coretta Scott King Award–winning illustrator Floyd Cooper depicts young Ira Aldridge watching a Shakespeare performance from the balcony of the theatre. Although laws about racial segregation were still evolving in the early nineteenth century, Black patrons at New York’s Park Theatre, as at most other playhouses, were relegated to limited seats in upper levels. Aldridge would later go to Shakespeare performances at the influential, if short-lived, Black-owned African Grove Theatre nearby and perform with its troupe, The African Company, before heading overseas to shape his own future.

![<div class="ira-title">English Heritage Blue Plaque unveiling ceremony at the site of the Coventry Theatre, Warwickshire, August 3, 2017</div>

<div class="ira-detail"><a href="https://warwick.ac.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases/against_prejudice_ira/" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">photographs courtesy University of Warwick</a></div>

<div class="ira-comment">150 years after Aldridge’s death the city of Coventry, England, unveiled an official historic marker (known in the U.K. as a “Blue Plaque”) to recognize his achievements there. Aldridge had gone to Coventry on tour in 1828. At that time the Coventry<i> Observer</i> reported that Aldridge “possess[es] a voice [which is] as fine, flexible, and manly as any on the London Stage. His action is unconstrained, and his knowledge of stage business and general effect that of a veteran . . . The text was understood and perfectly delivered . . . he has the intellectual susceptibility to feel the sentiments he utters and professional skill to give them forcible expression . . . We heartily wish him success.” Although he was only 21 years old at the time, he became the theater manager and spent a year running its operations, overseeing renovations, and programming a successful series of productions. The Blue Plaque today marks the site where the Coventry Theatre building once stood and commemorates Aldridge’s achievements. Among those who advocated for the placement of the Blue Plaque and assisted with the unveiling was the distinguished Black British actor Earl Cameron, CBE, who studied voice and performance early in his career under the guidance of Amanda Aldridge, Ira Aldridge’s daughter from his second marriage.</div>](https://www.chesapeakeshakespeare.com/wp-content/uploads/cache/ira-img-2727A/3290818555.jpg)

English Heritage Blue Plaque unveiling ceremony at the site of the Coventry Theatre, Warwickshire, August 3, 2017

150 years after Aldridge’s death the city of Coventry, England, unveiled an official historic marker (known in the U.K. as a “Blue Plaque”) to recognize his achievements there. Aldridge had gone to Coventry on tour in 1828. At that time the Coventry Observer reported that Aldridge “possess[es] a voice [which is] as fine, flexible, and manly as any on the London Stage. His action is unconstrained, and his knowledge of stage business and general effect that of a veteran . . . The text was understood and perfectly delivered . . . he has the intellectual susceptibility to feel the sentiments he utters and professional skill to give them forcible expression . . . We heartily wish him success.” Although he was only 21 years old at the time, he became the theater manager and spent a year running its operations, overseeing renovations, and programming a successful series of productions. The Blue Plaque today marks the site where the Coventry Theatre building once stood and commemorates Aldridge’s achievements. Among those who advocated for the placement of the Blue Plaque and assisted with the unveiling was the distinguished Black British actor Earl Cameron, CBE, who studied voice and performance early in his career under the guidance of Amanda Aldridge, Ira Aldridge’s daughter from his second marriage.

Exhibit content on this microsite is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.